I was just looking at some old photos from this time last year. A year ago the weather was a lot better and I finally made it to Bletchley Park.

I was just looking at some old photos from this time last year. A year ago the weather was a lot better and I finally made it to Bletchley Park.

It filled me with chest-thumping patriotic pride to think of these code-breakers puzzling over intercepted nazi messages, and inventing brilliant machines to break the code. A good old bit of government snooping and breaking encryption. hurrah!

It was a curious coincidence to return home on the same day, and see on the evening news, the home secretary Amber Rudd declaring that it was “completely unacceptable” that the government could not read messages protected by end-to-end encryption. There had been a small terrorism incident in which a few people were killed by a nutter with a gun at Westmister. Hardly deserving of the ‘T’ word. Apparently he had sent a WhatsApp message. So naturally this was being used as an excuse to enlarge government snooping powers. A good old bit of government snooping and breaking encryption. hurrah!

The enigma code was a different matter though. British code-breakers versus the nazi war machine.

It’s a well known story, but I learned a few things at Bletchley park, particularly while putting my stupid questions to a member of staff. I asked about what came before enigma. Radio signals had been extensively encrypted by various communication networks of the German military for years before the outbreak of war, and Poland had been extensively snooping, mapping out all these networks (a complex challenge in itself), and breaking various levels of encryption in a cat ‘n’ mouse game. They were able to pass on all of this information to the Brits. We were only carrying on with the game.

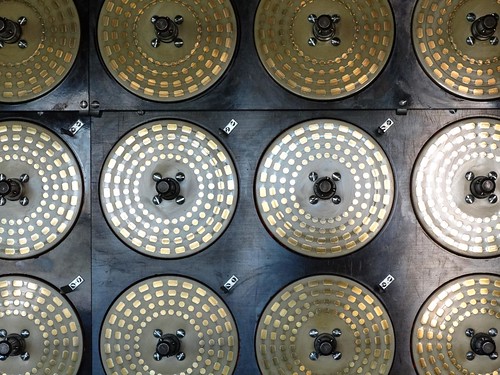

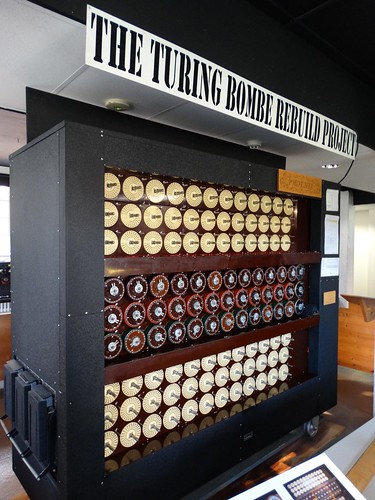

But with enigma machines the nazis thought they had an unbreakable code. To crack it, Alan Turing built the Bombe. This is often described as a forebear of modern computers. The star attraction at Bletchley Park is a working (moving!) replica. It moves with spectacular spinning and clunking noises. Watching the way it moves, it’s obvious that the spinning drums are performing a kind of brute force attack, trying every combination to break the encryption. But the replica is not complete, and actually seeing behind the drums where they are still missing, is very revealing. Metal brushes on the back of the rotating drums, brush over these metal contact pads. Behind the scenes they’re wired up so that an electrical current flows and the machine suddenly stops when it hits upon the correct combination.

I was amazed and delighted by the simplicity of that idea. The whole giant contraption is just a great big electrical circuit, with some mechanical movement thrown in. We can see and understand the machine at a very low level, in a way which is much harder with modern computers. In computer science studies we learn about all the lovely layers between applications like this web browser, right down to… well ultimately an electrical circuit. However I actually deliberately chose a computer science degree course which didn’t involve hardware, because I found that low level stuff uninteresting. I have a vague understanding, but maybe I should try building tetris with nand gates some time!

Although there’s a beautiful electromechanical simplicity to the Bombe, the less low level aspects (the details of the cryptography problem it’s actually trying to solve) are harder to understand. There’s a good numberphile video explaining some of it.

To come up with these solutions in 1940, Turing was surely a genius. He clearly knows the necessary hashtags. We rewarded him with chemical castration as a punishment for being gay, which drove him to suicide. Hurrah Great Britain!